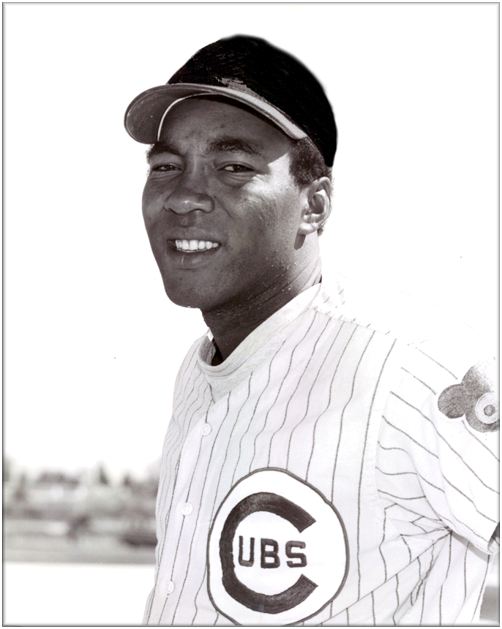

Jophery Brown

This righty pitcher’s big-league career consisted of just one game with the 1968 Chicago Cubs. His baseball days ended after the following season because of a rotator cuff injury – but the Grambling alumnus then turned to an exciting new life as one of Hollywood’s top stuntmen.

Jophery Clifford Brown was born on January 22, 1945, in Grambling, Louisiana.1 His parents, Sylvester and Ida Mae (Washington) Brown, married at the ages of 18 and 16, respectively. They had a family of eight, including four other boys (Alfred, twins Calvin and Galvin, and John) and three girls (Gloria, Rebecca, and Rayful). Jophery was the seventh child.

Sylvester and Ida Mae came from Farmerville, which is about 25 miles northeast of Grambling, and moved to Grambling in 1938, about seven years before Jophery was born. Sylvester, known popularly as “Sutton,” was a laborer. As Jophery’s future college teammate Ralph Garr remembered, though, the Brown family was better off financially than many others in the area because Sutton owned rental properties.

Older brother Calvin Brown – the pioneering black stuntman2 who paved the way for Jophery – described their upbringing as “community raised,” meaning that everyone in Grambling was responsible for raising the children. He said, “You could do no wrong, somebody was going to get you.”

As a youth, although Jophery played football and basketball too, he liked baseball best. He attended Alma Brown Elementary School and Grambling High School. A high-school teammate and friend named Johnny Gray remembered, “He was a heck of an athlete, nice person and he’d help you out in any kind of way you wanted. He was a perfectionist. He would always make sure you were prepared, in shape, conditioned, and [he] made sure you did your job.”3 Ralph Garr, who was then an opponent at Lincoln High School, said of Brown, ““He was what you called a premier pitcher. When we played against one another, he had some kind of ability, he had a fabulous arm.”

In 1963 Brown entered Grambling College (it became a university in 1974). Brother Calvin had graduated from there in 1957. A dozen Grambling Tigers have made it to the majors over the years, and Brown played with three of them: Garr, John Jeter, and Matt Alexander. Their coach was Ralph Waldo Emerson Jones, known to all as Prez because he was also the college president. Brown summed up this man with one simple and fitting word: “Great.”4

In 1963 Brown entered Grambling College (it became a university in 1974). Brother Calvin had graduated from there in 1957. A dozen Grambling Tigers have made it to the majors over the years, and Brown played with three of them: Garr, John Jeter, and Matt Alexander. Their coach was Ralph Waldo Emerson Jones, known to all as Prez because he was also the college president. Brown summed up this man with one simple and fitting word: “Great.”4

The Sporting News reported that during his career at Grambling (1964-66), Brown’s won-lost record was a spectacular 26-1.5 That appears to have been an exaggeration, according to the available school records – but his marks were impressive nonetheless. The known totals are 12-2 with a 0.88 ERA, including a no-hitter against Texas Southern in 1966 and five one-hitters. One of his few defeats came against archrival Southern University.

The Pittsburgh Pirates selected Brown in the 21st round of the June 1965 amateur draft, but he did not sign. As a result, he was eligible for the secondary phase of the following draft, in January 1966. The Boston Red Sox wanted him in the fourth round, but again he decided to stay in school. The offers were not attractive enough.6 (He didn’t necessarily want to graduate first, Brown said in 2010.)

In 1964 Jophery got his first exposure to the world of show business, thanks to Calvin. He appeared (uncredited) as a policeman in an episode of the Ben Gazzara/Chuck Connors drama Arrest and Trial. Right then he was bitten by the show-biz bug.

The following year, Bill Cosby became the first African-American to star in a television series. Before that, when black actors needed a stunt double, a white man put on blackface (“painting down,” as the practice was known). Cosby changed that on I Spy, insisting that Calvin Brown get the job. In 2009 Calvin’s friend and fellow stuntman Willie Harris said, “[Cosby] refused to let a white man double for him.”7 Jophery also did stunts, uncredited, in some episodes, while appearing onscreen as a reporter in one.

Brown’s stock continued to rise with big-league scouts. After his junior year at Grambling, the Pittsburgh Courier (an African-American newspaper) published two articles about his exploits. One said that rival coaches in the Southwestern Athletic Conference viewed him as a better prospect than Tommie Agee, then in his first full big-league season, who had starred for Grambling in 1961. It also quoted the college’s director of athletics, Eddie Robinson (better known as the coach of the highly successful Tigers football team). Robinson called Brown “the best-looking college pitcher I have seen” and “a dedicated athlete, with utmost confidence in himself.”8

The Cubs selected Brown in the second round of the secondary phase of the June 1966 draft. It’s no surprise that the scout was legendary Negro Leaguer Buck O’Neil, who signed a number of very talented young black players in the Deep South for Chicago.9

Jophery signed for a bonus estimated at anywhere from $40,000 to $90,000.10 He reported to the Cubs’ Rookie League team, Treasure Valley in Caldwell, Idaho. He appeared in 15 games in 1966, starting 14 and going 4-4 with a 3.72 ERA. He struck out 81 men in 75 innings – but also walked 59.

Brown moved up to Lodi in the high Class A California League for 1967. Eight men from that pitching staff would go on to the majors, most notably Jim Colborn. That May the Nevada State Journal, a newspaper in Reno, singled out three of them whose grand total in “The Show” was just five games: “Brown, [Alec] Distaso, a bonus rookie, and former Santa Clara frosh star Pat Jacquez are the fastest of the Crusher moundsmen.”11

There was a shortage of housing in Lodi, an agricultural town, and so Brown wound up sharing an apartment 15 miles south in Stockton with two other black players, Jim Atterbury and Mike Jones. The team’s Japanese-American general manager, Cappy Harada, made a point of dismissing a brief racial controversy.12

Jophery was the starter on Opening Day 1967.13 He pitched well, won, and got off to a 5-2 start. In a game at Bakersfield, though, a line drive struck him on the middle finger of his throwing hand. He stayed in the game despite being unable to grip his breaking pitches. “That’s the worst thing I did,” he said in 1968. “I shouldn’t have stayed in.” Even so, his record stood at 7-4 when he was hit in the wrist at Modesto. “I was able to throw, but with no authority after that. And everything I threw kept coming up.”14

Brown lost his last 13 decisions in a row, finishing the year at 7-17, with a 4.47 earned-run average. Lodi manager Jim Marshall worked with him over the winter and bolstered his confidence the following spring after Brown returned to the Crushers. “He sat down and showed interest in me as a person as well as a ballplayer. He instilled the desire in me.”15

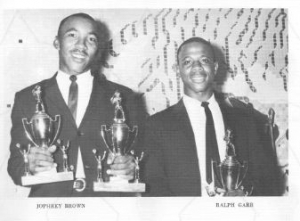

Jophery responded with a fine year in 1968. He got off to an 11-1 start, finishing at 18-9, with a 3.63 ERA. He was a unanimous choice as a California League All-Star (as were Ted Simmons, Tom Robson, and career minor-leaguer Joe Patterson).16 The Lodi Crushers Boosters Club named Brown the team’s Most Valuable Player. Jim Marshall accepted the trophy on his behalf, though, because he had earned a promotion to Triple-A Tacoma.17 There he was 0-1 in two starts.

Then, about a week later, Chicago called him up. Jophery made his lone big-league appearance on September 21. It was a Saturday afternoon game at old Forbes Field in Pittsburgh; entering in the fifth inning, Brown was the third Cubs pitcher in a game in which they trailed 4-1. Maury Wills greeted him with a single. After a sacrifice, a flyout, and an intentional walk to Roberto Clemente, Donn Clendenon singled in Wills. Brown retired the Pirates in order in the sixth, and then came out of the game. He did not get another chance to pitch over the remaining six games of the season.

Brown went to Instructional League that fall and then to camp with the Cubs in 1969. He received an entry in The Sporting News Official Baseball Register, which noted that his hobbies were bowling and reading wildlife books. That March, Baseball Digest’s scouting report read, “Cubs will give him thorough spring training look but figures to wind up in Triple A. Good competitor, and excellent poise. Also good size [6’2”, 190 pounds].”18

Jophery was indeed reassigned to the minors in mid-March, but he went to Double-A San Antonio. His 1969 season was just so-so: 9-10, 4.03. He may have been suffering from arm problems, but looking back in 2010, Brown commented tersely, “Didn’t care.” That was it for his baseball career. He recalled that he was traded to the Expos organization, but newspaper details are lacking.

Jophery followed Calvin – who had helped to found the Black Stuntmen’s Association in 1968 – into the business. (He never did graduate from Grambling.) In November 1969 the Long Beach Press-Telegram mentioned the Browns as actors in Bill Cosby’s production company. The occasion was a celebrity basketball game; Cosby sponsored and played. On hand were NFL star-turned-actor Bernie Casey, the Rev. Jesse Jackson, and Sammy Davis, Jr.19

In 2006 Jophery talked about his second career’s prerequisites. “You’re an athlete. You couldn’t be a stuntperson without being an athlete. You’ve got to have a degree of insanity to do this. But you didn’t want crazy stuntpeople. They get you hurt.” He also described how he developed his craft. “‘The business is trial and error. A lot you learn on the job. We couldn’t practice a lot of stuff because it was too expensive.’ He remembers being banned by Hertz because he would practice his stunt-driving in a rental car, and then invariably return it ‘slightly banged up.’”20

Brown got his first film work in 1973, the Pam Grier blaxploitation flick Coffy. He also had an uncredited bit part as a party guest. That year he also worked on Papillon, starring Steve McQueen, and the James Bond movie Live and Let Die.

An important professional breakthrough came thanks to a baseball movie, The Bingo Long Traveling All-Stars (1976). Thanks to his diamond experience, Brown was named stunt coordinator, although another black stuntman named Eddie Smith was reportedly displeased that Jophery had been chosen for this reason.21 This was probably because Smith, another founder of the Black Stuntmen’s Association, had more experience in stunt work. Jophery also played third baseman Emory “Champ” Chambers. The appealing film featured three other real ballplayers: Leon “Daddy Wags” Wagner, Indianapolis Clowns funnyman Sam “Birmingham” Brison, and Rico Dawson.

Before computer-generated effects came to rule moviemaking, Brown often appeared in several films a year. Just a few of the stunt-laden action-adventures on his résumé are Lethal Weapon, Die Hard, and Speed (in which he drove a bus over a gap in a freeway, something he discussed in an HBO documentary about the filming). Other credits as stunt coordinator include Scarface (he staged the gun battles) and Action Jackson.

Jophery also worked frequently in TV, including one of the great guilty pleasures, The A-Team. Along with doubling for Mr. T, he put his driving skills on display. The show had a distinctly cartoonish quality – in crash after crash, no one ever got hurt – which tended to obscure the difficulty of the “gags.” One trademark was a spiral vehicle flip, which Brown did more than 30 times.

In addition to his stunt work, Brown also continued to turn up frequently as a bit-part actor. One memorable moment came in Jurassic Park, when – as “Worker in Raptor Pen” – a carnosaur killed him. (“Jophery, raise the gate.”)

In 1990, Screen Actor magazine quoted Jophery, who emphasized the idea that led to the formation of the Black Stuntmen’s Association. “‘We get very few non-descript roles. . . . I pride myself in being able to do all types of shows, not just black films. And I do try to extend a helping hand to other qualified performers of color who are having a hard time of it.’ ” The magazine added, “Brown feels that people of color in power positions need to work with each other: ‘The black producers, directors and stars don’t always take care of their own by hiring black stunt coordinators.’”22

Brown discussed the nature of his work in 2006. “You can’t separate (stunts) into safe and dangerous categories. ‘All of them were dangerous. You could get hurt doing all of them.’ During the filming of the 1978 movie Convoy, he flipped an 18-wheeler. As it rolled, his seat belt came off. ‘I cracked three ribs, knocked my watch off and my shoes, too.’” He added, “Something hurts me every day.”23

From around 2000 or so Brown was semiretired; he doubled only for Morgan Freeman. (This brings to mind another former big leaguer: Greg Goossen, who was Gene Hackman’s stand-in for many years.) Jophery doubled for various other prominent African-American actors, such as Sidney Poitier, James Earl Jones, Danny Glover, Gregory Hines, Yaphet Kotto, and Denzel Washington.

In May 2010 Jophery Brown received the Taurus Lifetime Achievement Award for his body of work as a stuntman.24 At the time he lived in Las Vegas with his third wife, Lois Shannon. He had previously been married to Pamela Nocas (1970 to 1974) and Teresa Brooks (1984 to unknown date). He was the father of two children, Liana and Tyrone.

Brown moved to Santa Clarita, California in 2011. His last work onscreen came in the 2013 film Oblivion, co-starring Morgan Freeman. He died on January 11, 2014 from complications related to cancer treatment (he had been diagnosed about eight months before). His brother Calvin said, “He was one of the best guys you’ll ever want to know. He was a good brother and he was the greater voice of the family.”25

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Jophery Brown for his input (via mail, July 3, 2010). Thanks also to SABR members Jay Sokol (www.blackcollegenines.com) and Corey Stolzenbach (telephone interview with Ralph Garr, March 29, 2017), as well as Ethel Sims, niece of Jophery Brown. Biography updated in August 2017 .

Sources

Internet resources

Brief biographical sketch of Calvin Brown at the National Visionary Leadership project: http://www.visionaryproject.org/browncalvin/

http://www.retrosheet.org

http://www.imdb.com

http://www.classictvhistory.com

http://www.ancestry.com

Books

Grambling yearbooks, official yearly NAIA stat leaders, and the NCAA Official Collegiate Baseball Guide (courtesy of Jay Sokol)

The Sporting News Official Baseball Register, 1969.

Gene Scott Freese, Hollywood Stunt Performers. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co.: 1998.

Gene Scott Freese, Hollywood Stunt Performers, 1910s-1970s. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co.: 2014.

Photo credits

The Topps Company

Grambling College yearbook, 1966

Notes

1 Baseball references show the spelling of his first name as “Jophrey” – but it appears as “Jophery” in film references. Newspaper accounts during his playing days varied. Official confirmation is still pending, though Brown’s niece, Ethel Sims, has stated that “Jophery” is correct.

2 Kingsley, Amy. “Double standard.” Las Vegas City Life, November 17, 2008. In November 1962, Calvin Brown, who had been working as a postal clerk, was hired as an extra on a cheesy safari film starring Frankie Avalon called Drums of Africa. On the set he showed that he could do stunt work. See also Johnson, Erskine. “Avalon On Safari In California.” Evening Independent (St. Petersburg, Florida), October 20, 1962: 5-B.

3 Keise, Kevin. “Former Grambling resident dies,” The Gramblinite (school newspaper of Grambling State University), January 30, 2014.

4 For more detail, see Matt Alexander’s biography on the SABR BioProject site

5 Kranz, Dick. “Brownie Bounces Back for Crushers.” The Sporting News, June 29, 1968: 43.

6 Kranz, op. cit.

7 Fink, Jerry. “Locals honored for breaking a color barrier –in stunt work.” Las Vegas Sun, September 24, 2009; Kingsley, op. cit.

8 “Bo-sox High on Grambling’s Brown,” Pittsburgh Courier, June 18, 1966, 14.

9 “Grambling Ace Gets Bonus $$$,” Pittsburgh Courier, July 2, 1966, 15.

10 Kranz, op. cit.

11 Landell, Gib. “High-potential Crushers Invade Moana Tonight.” Nevada State Journal (Reno, Nevada), May 26: 1967: 11.

12 Kretzer, Dale. “Crusher Manager Says Race Had No Effect On Housing.” Lodi News-Sentinel, June 26, 1967: 1.

13 “Brown Selected To Pitch First Game For Crushers.” Lodi News-Sentinel, April 11, 1967: 8.

14 Kranz, op. cit.

15 Ibid.

16 “Brown-Lung Of Crushers All-Stars.” Lodi News-Sentinel, August 28, 1968: 20.

17 “Crusher Boosters Select Brown As Most Valuable.” Lodi News-Sentinel, September 4, 1968: 16.

18 “Official Scouting Reports on 1969 Major League Rookies.” Baseball Digest, March 1969: 19.

19 Willman, Tom. “Bill Cosby’s All Stars Cavort in L.B.” Long Beach Press-Telegram, November 18, 1969.

20 Padgett, Sonya. “Gotta Fight, Gotta Fall: Risk Takers.” Las Vegas Review-Journal, February 26, 2006.

21 Worsley, Sue Dwiggins and Charles Ziarko. From Oz to E.T. Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow Press, 1997: 135.

22 Screen Actor, Volumes 29-39. Screen Actors Guild: 1990.

23 Padgett, op. cit.

24 Thomas, Martyn. “Fast and Furious Drives Off with Taurus Awards.” Red Bull energy drink website (http://www.redbull.com/cs/Satellite/en_INT/Article/Fast-and-Furious-drives-off-with-Taurus-Awards-021242848884986), May 17, 2010.

25 Keise, “Former Grambling resident dies.”

Full Name

Jophery Clifford Brown

Born

January 22, 1945 at Grambling, LA (USA)

Died

January 11, 2014 at Inglewood, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.